The research project ISLAS studies the water cycle in the Norwegian Sea, and where the precipitation in Norway comes from during different weather events. This spring, the ISLAS scientists made simultaneous measurements at Andøya and other locations.

Isotopic Links to Atmospheric Water’s Sources (ISLAS) is a research project funded by the European Research Council that investigates the water cycle, including its processes during evaporation, transport and mixing, cloud formation and precipitation.

– The hydrological cycle, with its feedbacks related to water vapor and clouds, is a large source of uncertainty in weather prediction and climate models, says Harald Sodemann, professor in meteorology at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen and member of the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research.

This uncertainty is linked to several of the current major challenges in meteorology and climate research. These challenges include the forecasting of extreme weather events, preparing for the impacts of man-made climate change, but also the understanding of the paleoclimate record from the past.

However, using precise measurements of stable isotopes in water vapor, rain and snow, the scientists can find out where the water in precipitation comes from, and how it changes from liquid to solid or vapor, and back to liquid again, during its journey through the water cycle in the atmosphere.

A natural laboratory

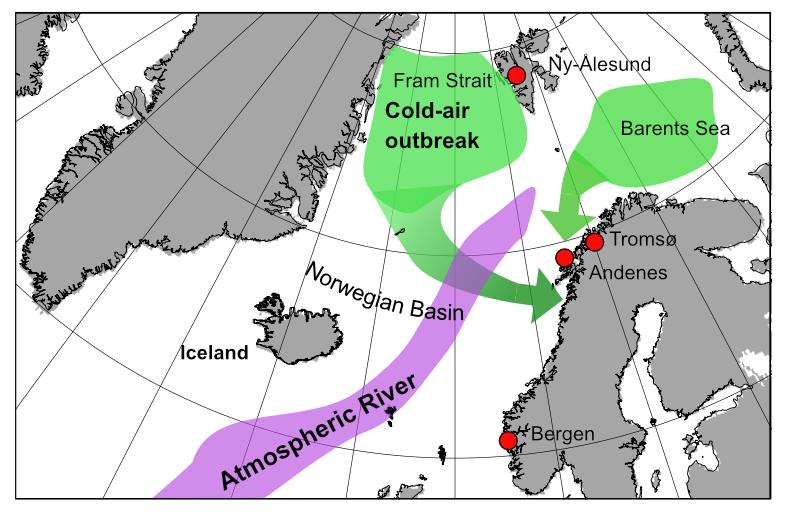

-Because the Arctic, the Norwegian Sea and the coast of Norway together create distinct evaporation events, shallow transport processes of water, and swift formation of precipitation, the entire water cycle can be studied here, says Sodemann.

This is why the ISLAS team visited Andøya Space and its atmospheric observatory Alomar. Together with colleagues from other universities, the ISLAS scientists used Alomar’s lidar and radar systems to investigate ice crystals in clouds and precipitation, and how they change from ice to rain.

The team also used their own instruments to measure the size and number of raindrops, the stable isotopes in water vapor, and other aspects of the water cycle.

– We brought a lot of instruments to Andøya in order to do many types of measurements at the same time in the same location, so that we can gain a detailed understanding of the processes of the water cycle here, says Sodemann.

Simultaneous measurements

The ISLAS instruments were located both at Alomar, at 380 meters height, and near sea level below the mountain where Alomar is located. In this way the scientists hoped to gain information about how much water raindrops absorb as they fall through the lower atmosphere, as well as data about other precipitation processes that take place on the way from cloud to ground.

In addition, the scientists had similar sensors in Tromsø, in order to detect the horizontal gradient between Andøya and Tromsø.

– Even though these locations are not that far apart, we nevertheless expect clear differences between them, for example the time when a storm arrives at both places, Sodemann says.

Other sensors are placed in Bergen on the west coast of Norway and at Ny-Ålesund in Svalbard in the high Arctic.

Improve weather forecasting

This year’s research campaign for ISLAS was intense, but short. Already on the 1st of April 2021 the scientists completed their measurements and returned home.

– We nevertheless expect to obtain the data we need, because the highly variable weather here at Andøya gives us many different meteorological events within a short period of time, says Sodemann.

He and the ISLAS team plan to return to Andøya next spring for more data from the same locations, while hoping to add measurements by plane and ship.

The results from ISLAS will be used to improve mathematical models of weather and climate, including short-term and high-resolution weather forecasting.

In addition to the participants from Norway, the ISLAS campaign involves scientists from universities and research institutions both in Europe and in North America.

– We see that close collaboration with scientists at other research institutions and in other parts of the world is very important to achieve our research goals. For us, it seems essential that what we do creates shared knowledge that benefits society as a whole, Sodemann says.

A service provider for science

– We are very pleased to welcome the ISLAS scientists to Andøya, says Michael Gausa, Director of Research and Development at Andøya Space.

Andøya Space aims to offer operational drone and aircraft services for scientists. Commercial drone operations, as well as training and certification services for these, are already well established. The drone services have a wide range of applications, from maritime surveillance and resource management to search and rescue operations, construction inspection and many more.

– The ISLAS campaign is an important step to complete our portfolio for scientific airborne operations. It enables us to listen closely to our guests in order to improve our infrastructure and knowledge, and to better reach the international research community and inform them of our drone services for scientific purposes, Gausa says.

Andøya Space has recently acquired an airplane, which in the future can perform in-situ and remote sensing measurements from the air, in the air, and of the air. This will open new doors for Andøya Space, which has a decades-long experience in sub-orbital launches of sounding rockets and research balloons and is building a launch site for small satellites.

Andøya and its location well above the Arctic circle, on the coast of the Norwegian Sea, is especially well suited for space, atmospheric and climate research.

– With our newly acquired plane we will soon have the capacity to be a full-service provider for scientific research that is dependent on measurements by drone or by plane, Gausa says.

More information?

Please contact Michael Gausa, Director of Research and Development at Andøya Space.